By Harrison Tasoff, UCSB

Groundwater is a critical resource around the globe, especially in dry regions, but it’s importance in sustaining ecosystems remains largely unstudied. There are many challenges in managing this precious resource for multiple purposes, including water supply and healthy ecosystems. New research has used satellite imagery and groundwater monitoring data to investigate the links between groundwater and the ecosystems they support throughout the state of California.

The study, published in Nature Water, underscores the pivotal role this resource plays in supporting groundwater-dependent ecosystems. The researchers, including UC Santa Barbara’s Michael Singer and Dar Roberts, identified how groundwater can be used to support ecological conservation within California’s Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA). Beyond highlighting groundwater’s significance, the study also offers an effective and practical approach for identifying where ecosystems are vulnerable to groundwater change and would benefit from more sustainable water use and management.

“Globally, there are increasing efforts to manage groundwater resources for multiple purposes, not only to support drinking water needs or high-value agriculture,” said co-author Singer, a professor at Cardiff University and a researcher at UCSB. “Our work provides a sound basis on which to develop clear guidelines for how to manage groundwater to support a wide range of needs within drainage basins.”

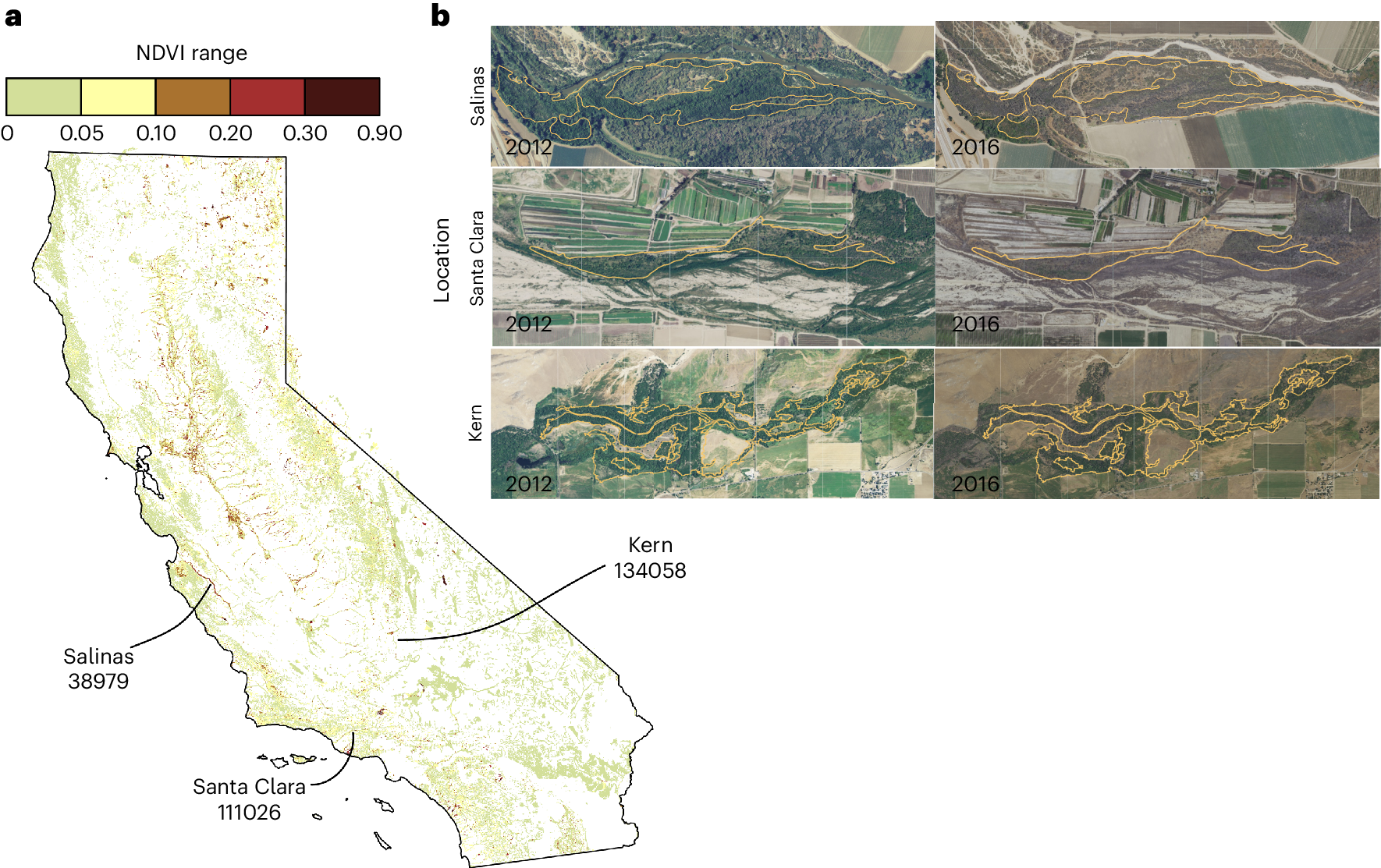

The study uses 38 years of Landsat satellite images (1985 – 2022) and statewide groundwater data to detect impacts on key plant species that rely on groundwater. These plants play a crucial role in supporting various ecosystems by providing habitat structure, producing biomass and regulating microclimate for both aquatic and terrestrial species. The study suggests that monitoring these plants can serve as an effective way to assess groundwater needs for ecosystems, informing decisions about water use and planning.

The study produced three important conclusions. First, the authors discovered that plants relying on groundwater suffered during the 2012 – 2016 drought, when water levels dropped. The researchers advise setting critical groundwater levels that consider these ups and downs.

The second was about how root depth affects ecosystem health. “We can use what we know about how deep the roots of different types of plants tend to be to approximate what groundwater levels are needed to maintain ecosystem health,” said Christine Albano, an ecohydrologist at the Desert Research Institute. “We found that vegetation was healthier where groundwater levels were within about 1 meter of maximum root depth, as compared to where groundwater was deeper.”

Third, the authors found that habitats dependent on groundwater serve as havens during droughts, supporting plant and aquatic life. They recommend safeguarding these areas, especially since only 1% of California’s vegetation is identified as a potential drought refuge.

“A vast majority of our planet’s freshwater is groundwater, but we don’t acknowledge or manage it sustainably, resulting in serious consequences for humans and natural ecosystems,” said lead author Melissa Rohde at Rohde Environmental Consulting, LLC.

Owing to its widespread availability, satellite imagery can be a powerful tool for investigating ecosystem impacts at landscape scales. However, it is challenging to detect critical thresholds where baseline conditions can be quite variable, such as groundwater-dependent ecosystems. A major innovation of the study was to use simple mathematical analyses of the greenness of vegetation to derive thresholds for detecting significant changes across a wide range of locations and conditions. Another key feature was to exploit the increasing resolution of satellite imagery and other geospatial tools to detect groundwater-dependent ecosystems such as isolated wetlands and narrow riparian zones, which historically have been difficult to isolate and delineate at large spatial scales.

“Groundwater is critical for many ecosystems, but their water requirements are rarely accounted for by water agencies and conservationists,” Rohde said. “To reconcile that, our study provides a simple, practical approach to detect ecological thresholds and targets that can be used by practitioners to allocate and manage water resources.”

This paper relies on technologies that weren’t really available to the scientific community until recently, especially over such a large area, explained co-author Roberts, a professor in UC Santa Barbara’s Department of Geography. “This type of study, covering the entire state of California over close to forty years, has really only become possible in the past few years and shows the promise for similar studies over a much larger geographic area using the approach pioneered by Melissa Rohde.”

“Groundwater-dependent ecosystems such as wetlands, floodplains and riparian zones have a very outsized importance on biodiversity,” said co-author John Stella, vice president for research at SUNY College of Environmental Science and Forestry. Sometimes upwards of 80 to 90% of species in a general region may be dependent on these ecosystems in some form or another. “Because groundwater-dependent ecosystems can be so small and scattered throughout the landscape, they’re hard to detect. And if they’re hard to detect, then they’re hard to protect.”

Karen Moore and Danielle Gerhart at SUNY-ESF contributed to this story.